Wetlands provide habitat for wildlife, filtration for water and even play a role in protecting us from drought. Now a group of Canadian researchers, including Drs. Larry Flanagan and Matthew Bogard from the University of Lethbridge, will study them to learn more about their exact role in combating climate change.

Led by Dr. Irena Creed, vice-principal of research and innovation at the University of Toronto, Scarborough, the project will build scientific understanding of wetlands, their function and the services they provide.

“There’s an assumption that nature is storing carbon to a certain degree, but we need stronger evidence to truly know how effective wetlands are as a nature-based climate solution,” says Creed.

“This work is highly relevant to southern Alberta and the Lethbridge area, because wetland protection and restoration is front and center in many discussions related to sustainable agriculture and watershed management,” says Bogard.

“This project is also key to broadening our knowledge about the part wetlands can play in mitigating climate change,” adds Flanagan.

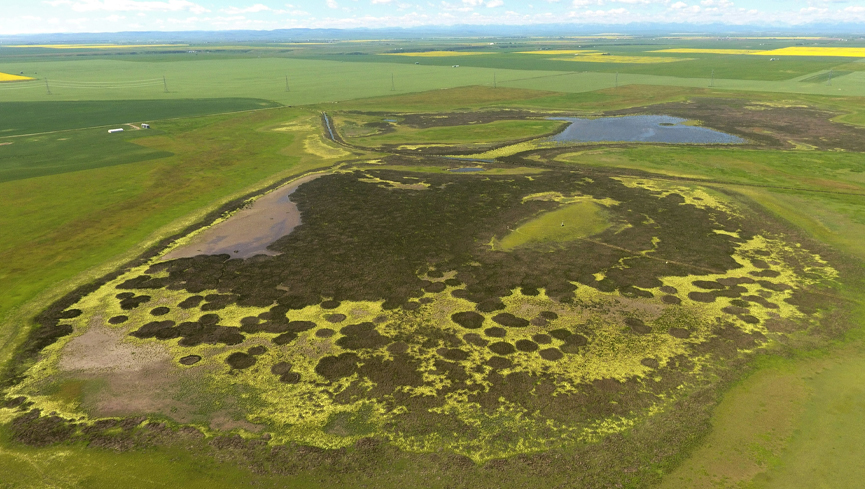

Wetlands offer essential ecological services for wildlife, humans and climate. They protect and improve water quality, provide habitats for fish and wildlife, store floodwaters and maintain surface water during dry periods. They store large amounts of carbon, which is a benefit to fighting climate change, but also emit large quantities of methane, an especially potent greenhouse gas.

By teaming up, Bogard, an aquatic scientist, and Flanagan, a terrestrial ecologist, will provide a more integrated, land-to-water picture of wetlands and how they cycle carbon and nutrients, with a focus on understanding the magnitude of net carbon sequestration relative to emissions of other greenhouse gases, such as methane and nitrous oxide.

Bogard and his team will contribute to the project by measuring greenhouse gas content in the water accumulating in wetlands across Canada, especially those in the Prairie Pothole region — an area of the Great Plains in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba with shallow wetlands that were created by glacial activity. By calculating the rate of emissions of the most potent greenhouse gases — carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide — the team will provide a comprehensive estimate of how wetlands influence Earth’s climate.

Flanagan and his team will bring expertise to the project by using a highly sensitive sampling technique called eddy covariance that continuously tracks exchanges of carbon dioxide and methane between wetlands and the atmosphere. In addition to measuring wetland greenhouse gas emissions, they will also assess wetland ecosystem responses to environmental conditions such as drought, warmer temperatures and nutrient pollution. This information will help to evaluate the contributions that nature-based solutions make to reduce the effects of climate change.

Creed says wetlands are among the most threatened ecosystems in the world, despite efforts to slow their rate of loss. Governments around the world have spent considerable money and resources rightfully trying to restore and rehabilitate them. At the same time, wetlands are being used as nature-based climate solutions without truly understanding the scale of their impact. What’s lacking is data showing at what point this strategy is good for addressing climate change.

“We need to fully understand the science behind it, to know what the tipping point is for storing carbon dioxide versus releasing more potent greenhouse gases into the atmosphere such as methane,” says Creed, a renowned ecosystem scientist.

The project is being funded in part by the Government of Canada’s Climate Action and Awareness Fund. The fund is an investment of $206 million over five years to support Canadian-made projects that help reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The partnership will include researchers from six universities from across Canada and seven non-academic organizations representing government and conservation agencies led by Ducks Unlimited Canada. An additional $4 million dollars will be invested in the project by various non-academic partners.